The villages

The villages is part of the following collections: The Harborough Collection.

Highlights

First Aid Nursing Yeomanry

Barbara Williamson was in the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry during the Second World War but the organisation was formed long before, even pre-dating the First World War. The ‘First Aid Nursing Yeomanry’ (F.A.N.Y.) was formed in 1907 as a link between field hospitals and the front line.

The name ‘Yeomanry’ came about because its members rode horses. Their founder, Captain Edward Baker, a veteran of the Sudan Campaign and the Second Boer War, felt that a single rider could get to a wounded soldier faster than a horse-drawn ambulance. This made it different from other nursing organisations as they saw themselves rescuing the wounded and giving first aid, similar to a modern combat medic.

Throughout the First World War they ran field hospitals, drove ambulances and set up soup kitchens and canteens for the troops and were involved in signalling and cavalry drilling. Many of the early women recruits were drawn from the upper middle classes.

During the First World War, two of the F.A.N.Y. nurses, Lieutenants Grace McDougall and Lillian Franklin, arrived in Calais driving motorised ambulances instead of the horses drawn ones. The British Army were slow to accept this so they drove ambulances and ran hospitals and casualty clearing stations for the Belgian and French Armies instead. By the Armistice, they had been awarded many decorations for bravery, including 17 Military Medals, 1 Legion d’Honneur and 27 Croix de Guerre.

Kelmarsh photograph

Kelmarsh is a small village in Northamptonshire, about nine miles west of Kettering. There are lovely stone cottages on the east side of the main road, where the original school was located and mostly red brick ones on the north side of the road to Harrington.

On the 4th May 1943 a tragedy struck the stone cottages. As lunch was being prepared in one of the cottages, a spark somehow ignited the thatched roof of the middle house. A strong wind was blowing, and all the 13 cottages were destroyed, making 44 people homeless. Fortunately, no one was injured, but all their possessions were lost. The cottages were rebuilt in 1948.

In 1849 Lord Bateman, owner of the village and occupant of Kelmarsh Hall, gave all his tenants notices, (these would be withdrawn if they signed an agreement promising to behave themselves in the future), because they had lapsed into bad habits and were constantly causing trouble.

The villagers were summoned to the Hall where they were ordered to attend church regularly and live in peace with each other, conducting themselves honestly and soberly. If the villagers obeyed, a school would be built so that their children would learn to read, write and do sums. A charge of 1d per child per week would be made. To honour this agreement, he built a school in 1850.

The Kelmarsh Tunnels are disused railway tunnels in Northamptonshire. The Northampton to Market Harborough line opened in 1859 and had tunnels at Kelmarsh and nearby Oxendon. The tunnels are 322 yards (294 m) long, and due to the smallness of the tunnel were known as “the rat-holes” by train drivers. The former “up” line tunnel at Kelmarsh is open as part of the Brampton Valley Way, which runs from the Boughton level crossing on the outskirts of Northampton to Little Bowden near Market Harborough, on the former railway track bed.

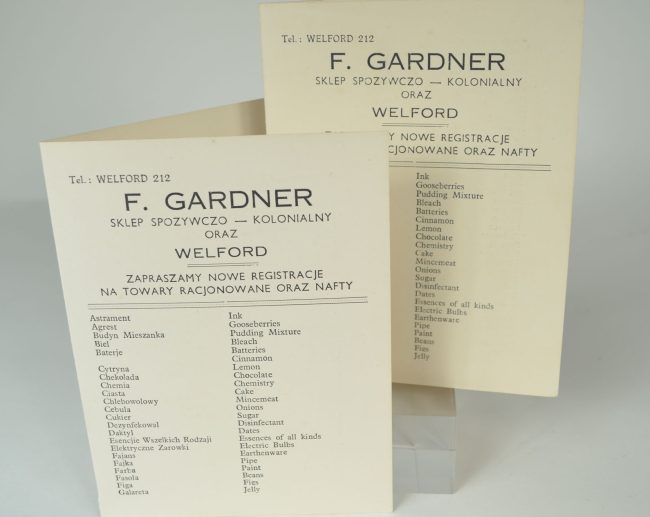

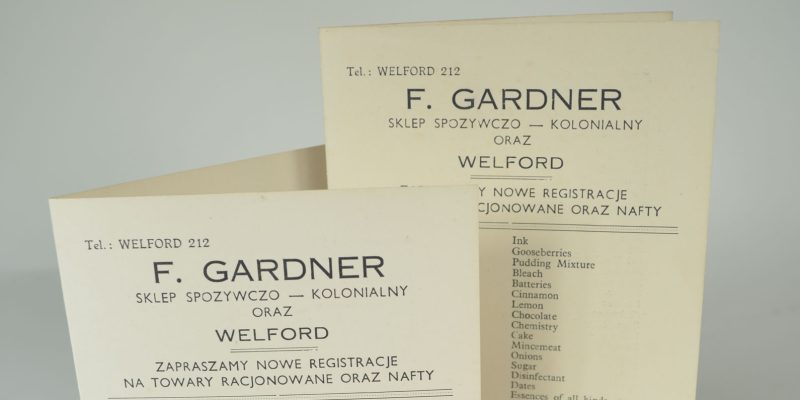

Translation card

This leaflet was produced, probably in the 1950s, for F Gardner’s grocery store in Welford. During the Second World War, people from countries including Poland, Czechoslovakia and Estonia were driven from their homes and travelled very far to find a safe place to live. After the war, there were many Polish families living in the area in the Sulby resettlement camp, which was then located between Welford, Sibbertoft and Husbands Bosworth.

During the war many Polish men joined the British Armed Forces and did not return to Poland. There were around 200,000 Polish people in Britain after the war and these camps were designed as temporary housing for them.

Most of the camps contained large Nissen huts made of semi-circular corrugated iron panels with brick work visible in the front entrance porch. These were very cold and were only heated by large black-leaded coal or wood-fuelled cooking stoves and paraffin heaters. Even so, communities prospered, children went to school and local jobs were found. Vegetables were grown to supplement their limited post-war diet.

Medieval Stirrup Ring

Stirrup Rings were fashionable from the 12th century to the 15th century and are defined by their simple elegance. The name ‘stirrup’ was first used by Victorian collectors during the 19th century due to the rings shape resembling horses’ stirrups.

The ring on display at Harborough Museum consists of gold and is formed in a ‘D’ shape, raising to a sapphire setting.

This style of ring was popular with bishops, as the gems used traditionally had religious significance. The ring would be worn on the middle finger of the right hand, sometimes over gloves.

During the Middle Ages jewellery was a symbol of status for the nobility and wealthy, showing their position in society. It was during the 14th century that Sumptuary Laws were initiated, limiting the amount of gold, silver or gemstones commoners could own. These laws were meant to curb opulence and promote frugality by regulation.

Further displays

Born and bred

Read more about 'Born and bred'

Growing up

Read more about 'Growing up'

Living off the land

Read more about 'Living off the land'

Made in Harborough

Read more about 'Made in Harborough'

Market Harborough and the District

Read more about 'Market Harborough and the District'

Market Harborough Historical Society

Read more about 'Market Harborough Historical Society'

Places to go, people to see

Read more about 'Places to go, people to see'

Religion and belief

Read more about 'Religion and belief'

Sickness and health

Read more about 'Sickness and health'