Born and bred

Born and bred is part of the following collections: The Harborough Collection.

Highlights

Ernest Elliott's marionettes

Elliott learnt how to play the piano by ear as a child and put on Saturday afternoon shows with his friends. He studied conjuring tricks, ventriloquism and had a Punch & Judy show. At the age of 18, he formed the Merry Vagabonds Concert Party, which performed locally until World War I.

His parents viewed his penchant for entertaining as “silly nonsense”. Therefore, after leaving school, Elliott worked for the family’s tailoring business on Church Street. After World War I, and his father’s death, he ran the shop with his mother. It prospered for a few years but ran into difficulties in the early 1920s.

During this time, he continued performing semi-professionally, but longed to do something more novel. Elliott had been watching a Leicester performer called John Goddard for some time, whose act involved human marionettes. When Goddard retired, Elliott took his place.

Elliott’s friends helped him acquire the equipment he needed for his act. One friend, a cabinet-maker, made him a marionette theatre, another helped him make the figures’ bodies and Elliott made the figures’ costumes.

His first paid performance was in 1922. He went on to become a great success and employed someone to run the tailors while he travelled the country with his show. At the height of his career he performed for Princess Margaret and made several television appearances.

Having toured the country for 35 years, Elliott retired in 1957. He is remembered by many as one of the best-loved entertainers from Leicestershire.

You can see photographs of his performances alongside the marionettes in the ‘Born and Bred’ case at Harborough Museum.

Gold basket hair ornaments

These rather unassuming objects can be easily overlooked. They probably don’t look like much, a piece of bent metal. However, when you hear they date back to 2,500 BC, you may give them a second thought.

The purpose of these ‘basket ornaments’ – ‘basket’ refers to their shape – is thought to have been as a hair piece. How can we possibly know what people 4,000 years ago would have used these for? We can’t. Despite this, an educated guess, using evidence of the Amesbury Archer who was found with similar ornaments by his head rolled to possibly secure hair, suggests that these were hair pieces of sorts.

What is amazing about these small but significant pieces is the fact that they are the oldest known metalwork in Leicestershire (and some of the oldest in the country). Found in Gilmorton in 2006, it is difficult to picture what the area and its inhabitants looked like in 2,500 BC; after all, we have as much evidence of Bronze Age Britain as we have of the last Ice Age – very little. It is fascinating when you realise that evidence like this proves just how early developed civilisations have lived in Britain. As a country, we were inhabited considerably later than others and it can be easy to assume that in 2,500 BC we were relatively primitive. However, these basket ornaments prove otherwise – they’re evidence of practicality and culture, objects beyond necessity.

When we talk about the Bronze Age, what image comes to mind? Perhaps it conjures up scenes of the Mycenean world; the Trojan War; the beautiful Helen of Sparta. Indeed, when Schliemann famously excavated Hisarlik – the site of mythical Troy – his finds consisted of such delicate golden trinkets. Although the layer to which Schliemann dug was earlier than that of the Trojan War (he dug to Troy) hence dispelling his claim that these were Helen’s jewels, it is in fact a period in which these basket ornaments date back to. The Bronze Age spanned a fair period, the legendary Trojan War took place in 1,200 BC whereas these objects are about 1,000 years earlier. It is no coincidence that the basket ornaments in Britain and the gold discovered at the Mycenean site date to the same period; it is suggestive of an explosion in innovation and perhaps is evidence for trade and links between the distant lands – although more likely that these skills were received from mainland Europe.

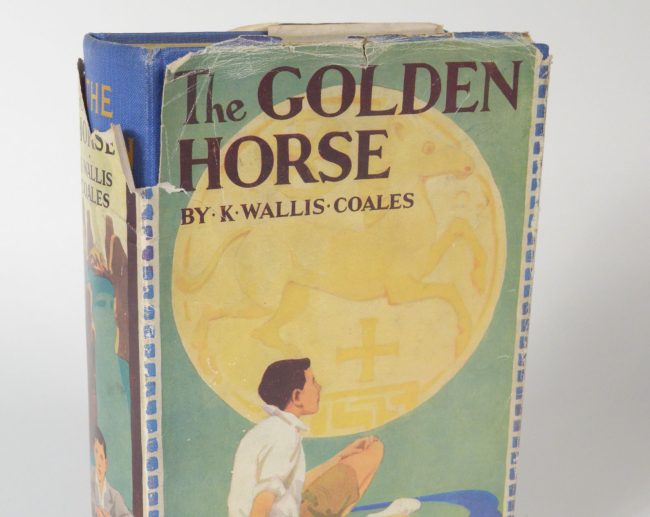

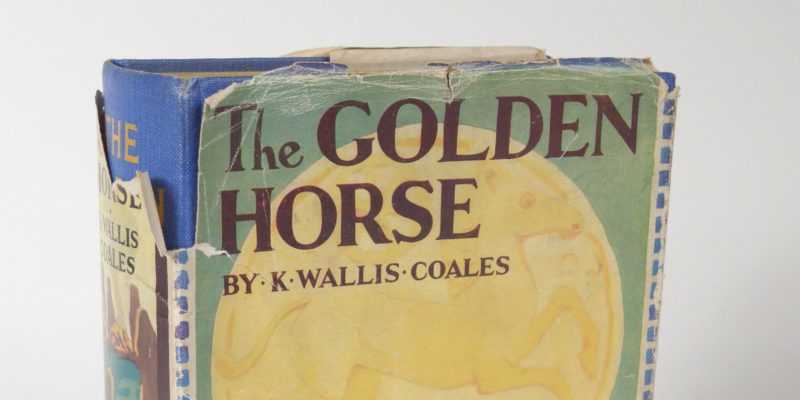

Kathleen Coales children's books

Kathleen Coales was a well-known artist, book illustrator and author of novels, poems and short stories. She lived with her family in their home on Burnmill Road. Her father, Herbert George Coales, was Chief Architect for the Council. He also wrote books under the name of ‘Mark Harborough.’

Kathleen Coales was a founding-member of Market Harborough Art Club, established in 1963. She received significant praise for her artwork, and her paintings were often displayed in Leicester Art Gallery. Following her death, the Art Club organised a memorial exhibition showcasing her work, which was sold for charity.

Along with others of her family, Kathleen was an active member of the Congregational Chapel and of the Scouting movement.

She wrote nine children’s books:

- The Dodo’s Egg (1923)

- The Wharfbury Watch-dogs (1930)

- The Pennyfound Puzzle (1931)

- The Monkey Patrol (1932)

- The Golden Horse (1934)

- The Secret of the Fens (1935)

- The Mascot at no. 7 (1936)

- Patricia at the Wheel (1937)

- Up with the Falcon (1938)

Roman lamps

Lamps provided the most common form of lighting in Rome. They were used for lighting in public and private buildings, as gifts to the gods in temples, and lighting at festivals.

Oil lamps were one of the most common household items of ancient times. Ceramic lamps were used to burn oil, usually a plant oil such as olive oil, that was abundant and accessible.

The lamp used a wick, made from fibres such as linen or papyrus, that was inserted into the lamp holder. The end of the wick rested in the nozzle. The oil was then poured into the lamp though the filling hole on top of its body. The wick was lit and a small flame was emitted from the tip of the wick resting in the nozzle. The lamp could be set on any flat surface but was also portable and could be carried in a person’s hand, which is why there were small lamps too.

Aside from their use for indoor and outdoor illumination, lamps also served other purposes. They were buried in tombs and graves along with pottery, jewellery, and other symbolic gifts.

Roman pottery

Pottery was an important part of daily living in ancient Rome. Romans used earthenware for most purposes including utensils, cooking pots and fine ware.

Originally Roman pottery was influenced by Etruscan and Greek style but later on established its own separate identity. Different types of pottery include:

- Amphorae: Roman amphorae were pottery jars which could be sealed and were used to carry different liquids and food items like olive oil, fish sauce and wine. These were usually large and undecorated but sturdy, well used and essential everyday pottery items.

- Coarse Ware: coarse ware pottery was mass produced, coarsely made and was used for different purposes like cooking, carrying liquids and eating (these were usually used by poorer people). Their quality was low, and they were thick enough to withstand rough use in kitchens and other places but still often broke.

- Fine Ware: this pottery was more carefully made. It was used by Romans for formal occasions and used to serve food directly on the table. It was delicate and thin, with an extremely glossy surface and some were even lead-glazed to make them look shiny. The richer you were, the more fine and ornately-made pottery you could afford.

Further displays

Growing up

Read more about 'Growing up'

Living off the land

Read more about 'Living off the land'

Made in Harborough

Read more about 'Made in Harborough'

Market Harborough and the District

Read more about 'Market Harborough and the District'

Market Harborough Historical Society

Read more about 'Market Harborough Historical Society'

Places to go, people to see

Read more about 'Places to go, people to see'

Religion and belief

Read more about 'Religion and belief'

Sickness and health

Read more about 'Sickness and health'

Sounds of Battle

Read more about 'Sounds of Battle'