Market Harborough Historical Society

Market Harborough Historical Society is part of the following collections: The Harborough Collection.

Highlights

Wedgwood loving cup

View object

Meteorites

View object

Double mouse trap

View object

Brisé fan with painted silk leaves

View object

Christening cup

View object

Drummer boy's jacket

View object

Egyptian statuette

View object

Fire fighter's helmet

View object

Lock for town stocks

View object

Mummified cat skull

View object

Bellarmine bottle

View object

Currier's slicker

View object

Door lock for No. 18 High Street

View object

Hopper bell

View object

Lord Rodney framed portrait

View object

Pattens

View object

Sun Fire plaque

View object

Wedgwood loving cup

Loving cups are shared drinking vessels, traditionally used at weddings or banquets. They have two handles and are often made of silver. Loving cups are also, at times, used as presentation trophies.

They date back to Saxon times when it was customary for anyone standing to drink from such a vessel to have a companion stand behind them for protection. This custom is said to have derived from the assassination of King Edward the Martyr in 978. It was recounted that the King was murdered whilst drinking from a vessel using both hands, and therefore vulnerable to attack.

Loving cups have a more sentimental symbolism when used in a marriage ritual. Here, they represent the cup of life, filled with the future possibilities of the bride and groom. The wine within contains sweet properties representing joy, peace and hope; and bitter properties symbolising sorrow, grief and despair. The combination of both signifies ‘life’s journey’, and all those who drink from the cup will share this happiness and burden. Loving cups are sometimes passed through generations.

The Wedgwood Loving Cup on display at Harborough Museum is likely made from Pearl Ware. Pearl Ware is an earthenware ceramic body with a slightly bluish white lead glaze, the result of a large proportion of white clay and small quantities of flint and cobalt oxide added to the glaze and body. It was developed by Josiah Wedgwood in 1779 to meet the competition of imported, blue-decorated Chinese porcelain.

The pattern, on this Loving Cup appears to be a combination of transfer-printing and hand-painting. Estimated to have been manufactured in the late 18th– early 19th century.

Wedgwood

Founded in 1759 by the potter and entrepreneur, Josiah Wedgwood, the company was soon one of the largest manufacturers of Staffordshire pottery, exporting across Europe, and as far as Russia and the Americas. The company was very successful at producing earthenware and stoneware, which was accepted as being of equivalent quality to porcelain, but much cheaper to purchase. In 1765, the company produced creamware – a lead-glazed cream-coloured earthenware – which became the main body of its tableware’s. After presenting a tea set to Queen Charlotte that year, she gave Wedgwood permission to call it ‘Queen’s Ware’. This new form was perfected as white ‘pearlware’ from 1780 and sold well in Europe and America.

Meteorites

Meteorites are solid pieces of rock usually made up of iron and nickel debris, typically from asteroids, comets or meteorites. They form in space and land on Earth after entering the atmosphere at high-speed creating shooting stars.

The museum’s small collection of meteorites were found on and around Beachy Head in Eastbourne, a popular place for people to find and collect fossils. The small village of Willingdon, six miles inland from Beachy Head experienced a meteorite shower which had been forecast in September 2004. A surprised local, whilst out walking with her dog, found a small piece of meteorite measuring around one and a half inches.

The largest meteorite shower ever recorded in British history, occurred in 1965 on Christmas Eve in the village of Barwell, Leicestershire. A local resident was out walking when he saw a flash of light and heard a loud bang, pieces of meteorite began to fall. Days after the shower the villagers began to collect a combination of small fragments and large chunks of the meteorite to piece it together. Much of the find has since been donated to the National Space Museum in Leicester.

For centuries we have been fascinated by astronomy, planets, UFOs and the workings of space. A local, notable resident from the village of South Kilworth, Leicestershire contributed immensely to research and development of our understanding of astronomy. Reverend Doctor William Pearson, born in 1767, co-founded The Astronomical Society in London in 1820 with fellow astronomer enthusiast Francis Baily; the society began pursuing research in astronomy, geophysics and the solar system. By 1831, the Society became the Royal Astronomical Society or R.A.S.

Double mouse trap

Norfolk Deadfall Mouse Traps were made from the Middle Ages to the 19th century. The wooden block would be lifted, and food put inside to tempt mice into the trap. In earlier versions the mouse would go into the trap and press down on a balance in the centre of the bottom board, triggering the heavy block to drop down and killed it.

It appears that the trap on display worked with metal springs, however, these have been removed at some point. This style of trap was not very effective, but they were cheap to make using pine, which could easily be cut and shaped. They wore out quickly, were susceptible to woodworm and most were thrown away, resulting in few surviving today.

Rat and mice infestations challenged the local authority in the 19th century. The Rats and Mice (Destruction) Act 1919 led to a local initiative from Leicestershire County Council. National Rat Week took place to encourage locals to make a concerted effort to exterminate the increasing infestations.

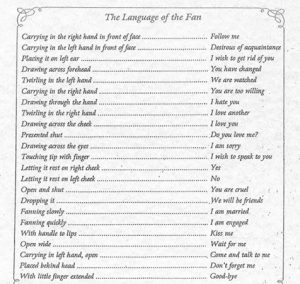

Brisé fan with painted silk leaves

One variant of the popular folding fan is the Brisé, meaning ‘broken’ in French. This type of fan has sticks which are wide and blade like, connected at the top by ribbon or thread so that they overlap when the fan is opened to form a leaf shape. The connecting material can be made of paper, lace or silk. The skeleton of the fan, the sticks and end guard sticks, is known as the ‘monture’.

This style of fan originates in 8th century Japan, through to Korea and coming to Europe via Dutch and Portuguese trading posts in China. However, hand fans date back over 4000 years ago in Egypt, where they were viewed as sacred objects. Tutankhamen’s tomb contained two elaborate hand fans.

In Western culture fans were commonly associated with the sophistication of the upper classes, symbolising wealth, power and status. In the Victorian era, a non-verbal system of communication evolved using the fan in social situations.

The Brisé Fan on display at Harborough Museum, is late Victorian, c1890, and made of ivory and painted silk with an ostrich feather trim. To determine whether the fan was ivory or bone we looked at the sticks under a magnifying glass; when looked at closely bone has tiny holes and is a little rough in appearance, whereas ivory has linear striations.

Part of fan seen through magnifier and light box.

Christening cup

Who was Annie Scott, you might ask. Was she a famous author, a painter, a poet? Was she perhaps a familiar face of the 19th century music hall, who graced the stage with her beautiful singing voice and performed in front of audiences of hundreds? The answer is in fact no, she was none of the above.

Annie Scott was born on the 8th of October 1853 in Market Harborough to Thomas and Sarah Scott. She was the youngest of 6 children, and her birth was commemorated with this charmingly decorated Victorian christening cup, a popular tradition at the time. Her christening was held on the 2nd of December the same year at St Dionysus church in the heart of town. Unfortunately, just a year after Annie’s birth, her father passed away. He left behind his wife and 6 children, including baby Annie.

In the 1861 census, 7 year old Annie was listed as living with her mother, her 5 siblings, her grandmother, and a servant boy called Olson. It appears that Annie’s mother, Sarah, kept her husband’s business going and was working as a glazier. Annie’s eldest sister, 20 year old Elizabeth, was working as a china dealer. Sarah and Elizabeth’s incomes combined meant that Annie was able to attend school.

10 years later, 18 year old Annie had moved to Leicester. She was by this time employed as a servant under the Marriott family. The head of the family was Sir Charles Hayes Marriott, a prominent surgeon at the time. Charles had become the house-surgeon at Leicester Royal Infirmary and, in a matter of years, had become known as the primary surgeon within the city. Due to his status, it is likely that he would have hosted important guests and meetings at his home, and Annie would’ve been around to witness them.

By 1881, Annie had left the Marriott’s employment and returned to her native Market Harborough. She had found work as a dressmaker and was living with her mother on Coventry Street. Sadly, Sarah died 2 years later. Annie subsequently moved out of their home and went to live with her older sister, Mary, and her family. She remained with Mary for at least 20 years, working as a domestic housekeeper.

Annie passed away in the winter of 1934, aged 81. According to the census, she never married nor had any children.

Though Annie was no Victorian celebrity, she was a Harborian. Her story, though not one of great excitement, should be remembered nonetheless because she is just as much a part of the rich Market Harborough tapestry as you. Her lovely christening cup, on display at Harborough Museum, serves as a reminder of one of Market Harborough’s people.

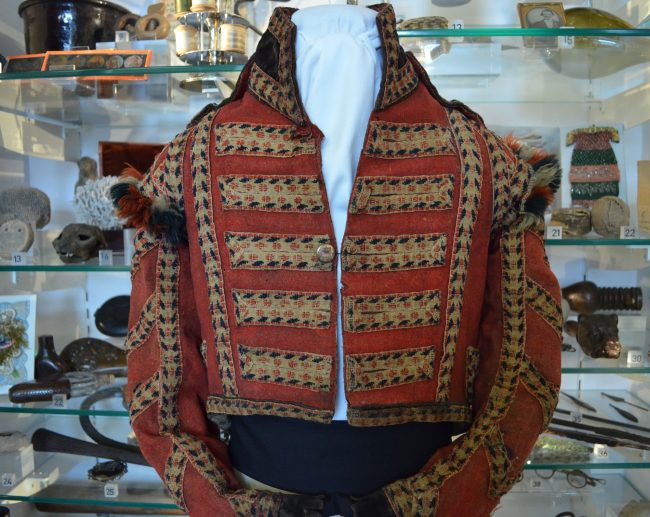

Drummer boy's jacket

The long war with Napoleonic France resumed on the 18th of May 1803 following the collapse of the Amiens Peace treaty. Soldiers and sailors were recalled to arms and county militia and yeomanry cavalry re-established. By June, France had begun preparations to invade England, so the British government called for volunteer infantry regiments to be raised. His Grace, the Duke of Rutland, Leicestershire’s Lord Lieutenant, was in command but companies of voluntary soldiers were to be organised at a local level.

On the 18th of August 1803 a public meeting was held in Market Harborough parish church and resolved that the town establish the’ Loyal Harborough Volunteer lnfantry, comprising two companies of infantry. Each company had a small band of drums and fifes. Volunteers had to be aged between 17 and 55 and they had to be vetted by a committee.

William French Major Esq. was appointed Captain Commandant of the First Company with William Atkins, Lieutenant and Thomas Green, Ensign. Pointz Owsley Adams Esq. was appointed Captain of the Second Company with Charles Heygate, Lieutenant and John Chater, Ensign. A full list of each Company is given in William Harrod’s, History of Market Harborough, 1808.

What we know about the Loyal Harborough Volunteer Infantry is that ‘officers and privates’ attended a theatre in the Town Hall on the 24th of September 1803 where songs were sung ‘with the warmest loyalty and patriotism’, The Companies received their Colours at a ceremony on the 13th of February 1804 and later that year, they were on ‘active duty’ in Melton Mowbray and in 1805, at Daventry. A number of soldiers of the 65th Regiment of Foot mutinied at Kettering and were marched, under guard to Market Harborough and the Loyal Harborough Volunteer infantry were ordered to escort the mutineers from here to Leicester.

Following the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, the threat of invasion was minimised, but the voluntary infantry units remained until 1808 when it was decided they were no longer required.

This drummer boy’s jacket dates to the final year of the Napoleonic Wars and represents just one individual who played one role. It was normal military practice in the early 19th century to recruit boys as drummers. This was important as they learned how to use drum rhythms and beats to signal the officer’s commands to his troops during the heat of battle. They also represented a rallying point against which the troops could be organised, as well as acting as a regiment’s mascot of sorts.

There are many questions surrounding this beautifully detailed jacket. Was the jacket ever worn in battle? Was the owner related to anyone in the regiment he served, the Market Harborough Volunteers? How old was he? Many boys ran away to join the military and often lied about their age to get in. The youngest recorded was 7! It’s quite a small jacket so it seems likely that he was relatively young.

The life of a drummer boy appeared rather glamourous and exciting to those at home. This, coupled with the evidence that sometimes boys followed their brothers to serve in the same regiment, may have been an incentive to sign up.

Egyptian statuette

One of the objects in our museum is fake. A genuine, Victorian forgery. This might seem a little odd to say but the historic value of the forgery is almost as great as the object it supposedly mimics. At the back of one of our cabinets is a statuette of an Egyptian figure and despite it’s convincing appearance at first glance it is, in fact, a Victorian era forgery. It is a historical artefact that helps us to explore the Victorian and Edwardian obsession with Egypt.

The British Victorians were entranced with the concept of Egyptian history, they took the time to indulge in all sorts of macabre events that centred around mummies and ancient Egyptian remains.

The rise of Victorian mysticism fed into the fetishization of artefacts and the ancient Egyptian way of life. This fascination on behalf of the Victorians is not surprising considering the ancient culture was so entwined with the concept of death and the afterlife. The Victorian desire to explore the macabre and the gothic feasted on the ideas they held of Egyptian culture; at the time there was a rise in seances and esoteric beliefs regarding death, this created a market for artefacts associated with these topics. Feasting was not just reserved for the conceptual and ethereal, no, the reasons that mummified remains are rare now is due to the taste that the Victorian people had for grinding up and consuming them. ‘Mumia’ originally was simply a ground up mineral, bitumen, referred to as mineral pitch. However, with the mistranslation it soon became acceptable to consider Mumia to mean embalming minerals scraped from mummified remains. It was only a short hop then to grinding up the entire mummy for medical consumption. In that light, maybe forging statuettes as souvenirs is a less macabre way of Victorians appreciating the ancient Egyptian way of life.

The fakes and forgeries were not always intended to deceive, in much the same way as we would purchase trinkets from museum gift shops, some were just recreations to bring home and decorate the house with. These replicas would have no false provenance and would be explicitly bought and sold as totemic representations of the artefacts they mimicked. This is where it muddies the waters: are all non-authentic Egyptian artefacts ‘fakes’ or could some just be considered replicas? The item in our museum though, is a definite forgery; a contemporary item that is claimed to have genuine ancient roots with intent to deceive individuals over its origins.

The desecration of ancient corpses however, was not limited to cannibalism. No, for Victorians gathering around with your friends and hosting an ‘unwrapping party’ was just a jolly weekend get together. An unwrapping party was simply the unscientific and anti-archaeological process of getting a mummy, getting your mates and… unwrapping the thing like a gift from under the Christmas tree. These events were focused on the performance and interaction with the preserved remains. This was a phenomenon diametrically opposed to our current ideas around preservation and collection within the heritage sector. Egyptomania influenced art and culture to such a degree that we can see it in the Washington monument in the USA, it was a fevered desire to explore the ‘foreign’ and the ‘other’ in a distinctly imperialistic manner.

After Napoleon’s wars in the region, the French founded research institutes and began excavations. They documented and unearthed evidence of the ancient civilisation as well as collecting hundreds of thousands of archaeological artefacts. However, after the French surrender the British seized the artefacts they had unearthed and in this claimed the famous Rosetta stone for the British museum. This then, became a point of pride and interest for the people and began the boom for the Egyptian artefact trade. It also helped to muddy the waters regarding the provenance of certain items, with them changing hands so often records became lost or misattributed. This only aided the ease in which forgeries could enter the market.

The romanticising of the ancient way of life, combined with nationalistic pride and a voyeuristic interest in death, the macabre and the occult fed a frenzy for ancient objects. This was the era of Egyptomania. Here then, we circle back to our Victorian forgery. In order to meet demand for the ancient objects unscrupulous dealers soon began the process of manufacturing items that would fit the needs of individuals who wanted something from a mysterious land they had no hope of ever seeing. The object in our museum tells us more about the frenzy that Victorians found themselves wrapped up in than it does about actual Ancient Egyptian culture.

Forgeries fuelled the Egyptian artefact trade, with even professionals being duped by the volume and standard of the fakes that flooded the market. Auctioneers occasionally lended a hand to inflate the importance or obscure the provenance of certain artefacts. Our little fake statuette tells us of the desire of the Victorian people to own and explore the ‘other’ and the ‘foreign’, to engage in spiritualism and mysticism. It may tell us nothing about ancient Egyptian culture or values, it certainly tells us a lot about the values of Victorian Britain at the time.

Fire fighter's helmet

This fireman’s helmet, from the early 20th century, is made from papier-mache. They were typically better for identification purposes than protection! Stronger brass helmets were also used, but as these conducted electricity, they were normally only worn at ceremonies.

Leather helmets, which were a lot safer, eventually replaced both.

Firefighting has been known in Market Harborough since 1679 when water was pumped manually from the Folly Pond, next to the present day fire station on Fairfield Road.

In 1870 a volunteer fire brigade was created with horse-drawn fire engines. But by the end of WWII locally organised fire brigades like this had been merged into the National Fire Service.

In 1903, a new fire station was built on Abbey Street which you can still see today with its distinctive red doors and polished tiles. Since the current fire station on Fairfield Road opened in 1989, the Abbey Street building has been home to a variety of businesses.

Lock for town stocks

The town stocks were to the rear of the Old Grammar School in Church Square, formerly Chapel Yard. The stocks were located near to the Old Guard House, as was the whipping post. Prior to the foundation of the police force, by Sir Robert Peele, personnel known as Charley’s or Watchmen withheld the law in the town. They were essentially early police constables.

During the 19th century, Market Harborough was a bustling little market town and vagrants often passed through its streets, some causing chaos in their stead. The stocks would’ve regularly held such vagrants; the whipping post beside it was certainly used frequently too. One account details how individuals would be tied to the post with their hands stretched above their heads, they would then have their backs whipped repeatedly until they could scarcely stand.

They were subsequently driven out of town and told to never return. The old Poor Law welfare system meant the parish where a person was resident was responsible for them, not where they were born: in order to reduce the cost of providing shelter and food, many parishes sought to drive out people who travelled from place to place, seeking respite.

By 1838, the Old Guard House, also known as the lock-up, had been entirely replaced by a brand-new police station. With the creation of a new police force, neither the stocks nor the whipping post was need any longer. It is likely that the stocks were dismantled. The lock is all that remains of what was once one of the town’s principle forms of punishment.

Mummified cat skull

Ancient Egypt had many customs and traditions. Cats were held in such high regard and worshipped, the goddess known as Bastet was presented as half-cat, half-woman. Cats, such as the one on show in Harborough Museum, would have been highly looked after, as it was a crime to hurt or injure a cat, punishable by death.

When the cat’s owner passed away however, it was often customary for them to join their owner in the afterlife; which meant they had to die too. This cat skull on display, dating from the 3rd century BC, has some significant damage to the left-hand side of its skull which could be indicative of a deliberate death. In many Egyptian burials, skeletal remains of cats have been discovered. This is thought to be because cats were seen as protectors, as depicted in the Egyptian Book of the Dead.

Just like their owners, cats were carefully mummified to preserve them. It is likely that this cat was very well-loved and accompanied his or her master to the afterlife.

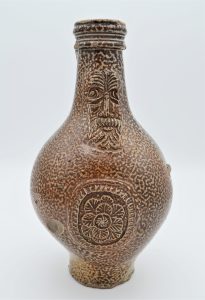

Bellarmine bottle

The Bellarmine bottle with a missing handle was found in 1955 under the floor of the Peacock Hotel in Market Harborough (now Pizza Express). The bottle has been dated back to the 16th/17th century when wines and beers were decanted from wooden barrels into stone jugs, bottles and pitchers for easier transportation.

The name ‘Bellarmine’ comes from the cardinal Robert Bellarmine who published anti-Protestant literature in Holland at the time, opposing the Dutch Reformed Church.

The signature decorative face seen on neck of the bottles are recreations of Bellarmine; It became popular for Protestants who disagreed with his texts to smash the jugs and shout his name!

The bottles were also known as ‘witch bottles’. People believed that filling them with iron pins, hair, urine and other charms, before sealing and burying them in their gardens, or placing them at entrances to their homes would protect them from a witch’s curse.

Of around 200 witch-bottles recorded in England, 130 are Bellarmines.

Currier's slicker

This object is what is known as a slicker, a tool used by a currier. Curriers are the individuals who finish leather after the tanning procedure, the final step in the tanning process before the material is passed on to the manufacturer. The process of currying is to colour, seal and finish the tanned animal hide so as to render the material robust and waterproof. The hide is then burnished before being dyed and subsequently finished.

We are lucky enough to have this photograph from Image Leicestershire, that shows a group of fellmongers operating in Market Harborough. Fellmongers dealt with hides and skins (particularly from sheep), preparing them for tanning. These men, from a photograph in around 1870, are soaking goat skins in lime pits in order to remove the hair before the skin was tanned to make leather.

This tool, the slicker, is used to smooth and polish the edges of the leather. It is moved in a back and forwards motion, not dissimilar to a nail file. This particular slicker, which once belonged to J. Dawbarn and Sons, is a larger and flatter slicker which suggests it might have been used for larger pieces of leather.

Door lock for No. 18 High Street

The High Street, running through the centre of Market Harborough, has long been the town’s beating heart. Each building dotted along the street has hosted several businesses over the years, and number 18 is no different. It is currently owned by the pub chain Wetherspoons, however, back in the early 19th century it was a grocery shop.

The shop belonged to Thomas Goodwin Goward and his family. Goward’s grocery shop thrived, it backed onto a warehouse which was used by members of staff to blend tea, grind coffee and spices, wash fruit, and dice sugar. The latter is where its current name, the Sugar Loaf, originates from. Sugar used to arrive at the warehouse in cone-shaped loaves and was then hand-diced to sell to the public. Goward, his family, some of his staff members and a couple of domestic servants resided above the shop until the late 19th century

Prior to Goward’s, the building was another grocery shop named Austin and Allen, and prior to that, in the late 18th century, it was a drapery owned by William Andrews. This large lock was attached to one of the doors at 18 High Street and dates back to the early 18th century.

Hopper bell

Though it might not look like much, this hopper bell was in fact quite a useful bit of kit for the 19th century miller. The hopper bell was situated within the windmill’s stone hopper, or millstone, which would crush the corn or grain to transform it into flour. Sacks of grain would have been hoisted to the top of the windmill and poured into a grain bin. Grain would then slide down a chute into the stone hopper. When the stone hopper was running low of grain, the hopper bell would scrap against the stone and emit a grinding noise. This noise informed the miller that the hopper was almost empty.

The hopper bell on display at Harborough Museum comes from Mill Hill, a windmill which used to be located just off St Mary’s Road, close to Symington Way. Not much is known about the windmill as it was demolished in 1895.

Lord Rodney framed portrait

This small painting, donated by the Market Harborough Historical Society, was painted around 1790, 2 years before George Brydges Rodney’s death. The painter is currently unknown, but Lord Rodney would have been a popular figure in his day and remains a popular figure in naval history to this day.

In January 1718, George Brydges Rodney was born in Walton-on-Thames to Henry Rodney and his wife, Mary. Henry was a war veteran, having served during the War of the Spanish Succession under the Earl of Peterborough just a few years prior to the birth of his son. He was also the reason why the family suffered such a dramatic decline in their financial status. Henry made a huge investment in the South Sea Company, which supplied African slaves to islands around South America and the Pacific. Once war broke out again in 1718, the company lost around £300,000 in assets and most investors, including Henry, lost vast amounts of their wealth. The family, though destitute, remained strongly connected due to marriage ties.

By 1732, 14-year-old George had joined the Royal Navy. He first served upon the HMS Sunderland, and subsequently the HMS Dreadnought, where he served as a midshipman. Within his first few years as a seafarer, he was posted to various places upon various ships including to Canada where he assisted in the protection of a British fleet of fishermen. In 1739, 21-year-old George had been promoted to lieutenant. He served under Admiral Sir Thomas Matthews but, a year later, the War of the Austrian Succession began, and George was sent to fight in Ventimiglia, northern Italy. He was shortly after promoted to post-captain and began serving upon the HMS Plymouth.

George’s naval career went from strength to strength relatively quickly. Upon the HMS Ludlow Castle, George was stationed around the Scottish coast during the Jacobite Rebellion of 1745. The following year, he captured a Spanish 16-gunner, and was later ordered to join Admiral George Anson around the French coast where he assisted in capturing 16 French ships. After the war, George returned to England where he received around £15,000 for his services. He also became elected as MP for Saltash, and married Jane Compton, the Earl of Northampton’s sister. Before her untimely death in 1757, they had 3 children together.

The year before Jane’s death, England entered the Seven Years War after a French attack on Menorca. In 1757, George sailed aboard the HMS Dublin as part of Admiral Edward Hawke’s raid on Rochefort. He was subsequently directed to sail Major General Jeffery Amherst across the Atlantic to oversee the Siege of Louisbourg, an attempt to capture the French fortress. Capturing a sailing ship en-route, George was later criticized for putting prize money ahead of his orders. Despite this, he was promoted to rear admiral in May 1759, and shortly after he took part in operations against French invasion forces at Le Havre. Employing bomb vessels, he attacked the French port in early July, which inflicted significant damage. George struck again in August, but the invasion plans were cancelled later that year after major naval defeats elsewhere.

By the 1760s, George was stationed in the Caribbean. He had been tasked with the command of a British expedition to capture the island of Martinique, and also managed to capture St Lucia and Grenada as well. He returned to England in 1763, where he was promoted to vice admiral. He remarried to Henrietta Clies, and began serving as the governor of Greenwich Hospital, also running again for parliament in 1768. In the early 1770s, George took up a commander-in-chief post to Jamaica. He arrived on the island, and worked to significantly improve naval facilities. Due to his bid for parliament back in 1768, which although he had won, had left him struggling for funds, he was beginning to feel the pinch. Fortunately, a friend lent him the money to clear his debts, which George was able to repay shortly after being promoted to admiral during the American Revolution.

By 1780, George had returned to the Caribbean. He captured at least 7 Spanish ships on the way, but during conflict with a French fleet, his signals were misinterpreted and his plans were unsuccessful. In 1781, George and General John Vaughan were captured on the island of St Eustatius. Once again, George was accused of putting wealth before orders as he shouldn’t have been on the island long enough to be captured. He returned to England where he staunchly defended his actions, and parliament sided with him. He returned to the Caribbean one last time in 1782, where he captured another 7 ships. His actions were revered, and were described as providing a boost to the British morale which had taken a knock due to several defeats over previous years. Upon returning to England once more, he was rewarded with the title Baron Rodney of Rodney Stoke. He retired from both service and public life soon after, and died on the 23rd of May 1792, aged 74.

Pattens

These pattens or overshoes, made from a combination of leather, metal and wood date back from around the 18th century. The metal ring affixed to the base of the patten was specifically invented to raise the individual above the street-level. It was designed in a ring shape to provide the wearer with balance.

They would have been strapped on underneath a pair of shoes and held in place with the leather fastening, elevating the wearer above the muddy and wet streets. As sanitation during this period was a far cry from today the streets would have been significantly dirtier, flooded with the draining’s of bedpans; the 18th century ‘toilet’.

Despite their practicality, pattens were deemed somewhat discourteous due to the incessant clinking noise they made when worn. In Jane Austen’s posthumous novel, Persuasion, Austen describes “the ceaseless clink of pattens” along with other everyday sounds to be heard in the early 19th century street.

Sun Fire plaque

Market Harborough had some way of fighting fire as far back as 1679, only 34 years after the Battle of Naseby. There was probably a large pump used by six people, and the water was taken from the Folly Pond, which is nearby the present-day fire station. Streams were made going down the hill to get water into the town, and an underground tunnel replaced this in 1766.

In 1870 a Volunteer Fire Brigade was created in the town, and horse-drawn fire engines were stored outside the church of St Dionysius. Smaller, private fire brigades were run by insurers and you could tell a business or building was covered by a mark or plaque, such as the Sun Fire one.

Local Government took over the Fire Brigade in 1880 and by 1903, the distinctive fire station on Abbey Street was built. The current fire station on Fairfield Road was opened by the Duke of Gloucester in 1989.

Further displays

Born and bred

Read more about 'Born and bred'

Growing up

Read more about 'Growing up'

Living off the land

Read more about 'Living off the land'

Made in Harborough

Read more about 'Made in Harborough'

Market Harborough and the District

Read more about 'Market Harborough and the District'

Places to go, people to see

Read more about 'Places to go, people to see'

Religion and belief

Read more about 'Religion and belief'

Sickness and health

Read more about 'Sickness and health'

Sounds of Battle

Read more about 'Sounds of Battle'