Market Harborough and the District

Market Harborough and the District is part of the following collections: The Harborough Collection.

Highlights

Cattle Market key

Harborough has officially had a market since 1203 when the King granted the town a royal charter.

View object

Cattle Market key

On market day the town was swamped with stalls and animals tethered and penned along the streets. Cattle gathered near today’s Angel Hotel many chained to posts still standing on the High Street.

More than 2000 beasts roaming the streets disrupted daily life considerably! Pedestrians were in danger of being trampled and piles of dung covered the town! The market ultimately moved to a site off Springfield Street as a result of public health concerns.

On April 14th, 1903, the new cattle market was opened, and this silver key was presented to J. L. Douglass Esq. (Chairman, Market Harborough Urban District Council).

The Settling Rooms are the only remaining part of the market. This building where farmers once settled their accounts with the market authorities, socialised and got refreshments, is now listed, and stands resplendent in the centre of Sainsbury’s car park.

Hallaton Bottle Kicking dummy

This bottle kicking dummy comes from the nearby Leicestershire village of Hallaton. It had a very important role in the wonderfully bizarre Leicestershire custom – the bottle kicking. This annual competition between the villages of Hallaton and Medbourne, usually held on Easter Monday, involves a team from each village attempting to get two bottles from the start at Hare Pie Bank across their home stream one miles away by any means possible. With virtually no rules and resembling a huge rugby scrum traversing ditches, hedges and barbed wire, the competition is notoriously bloodthirsty and it’s not uncommon for there to be broken bones! The Hallaton Village Chronicle (1938) reported: “There are broken heads and ribs occasionally,” but people still have lots of fun!

The proceedings begin with the parading of an enormous hare pie through the streets of Hallaton accompanied by a local band. The village’s vicar emerges from the church, blesses and carves the pie then distributes it to the waiting onlookers while a small portion is put in a sack to be used later in the ’Hare Pie Scramble’ where handfuls are thrown to the hungry scrambling crowd. When everyone has had their fill the two bottles are taken to the Buttercross and decorated with ribbons and in the afternoon the bottle kicking begins at Hare Pie Bank.

According to the museum records, this ‘dummy’ was used from 1850 to 1950 in playoffs when the score was one all. Made of solid wood and painted red, white and blue, it differed from the ordinary bottles which were miniature wooden casks of ale bound with iron bands.

Although records of bottle kicking only date to the late 18th century, it is believed by some to originate from much earlier and may be linked to the sacrifice of the hare in the Dark Age worship of the goddess Oestre. Yet, according to local lore the tradition began when two ladies of Hallaton were saved from a raging bull by a startled hare that distracted the bull. They showed their gratitude to God by donating money to the church on the understanding that every Easter Monday the vicar would provide a hare pie, 12 penny half loaves and two barrels of beer for the poor of the village. The Hallaton villagers would fight one another for the food and drink, and on one occasion the neighbouring village of Medbourne joined in and stole the beer! The Hallatonians cooperated to retrieve the spoils, thus beginning the village rivalry that continues to this day. In 1790, the rector tried to ban the event because of its pagan origins, but the next day, graffiti appeared on the vicarage wall: “No pie, no parson”. This led to the church joining in with proceedings and the event continues today.

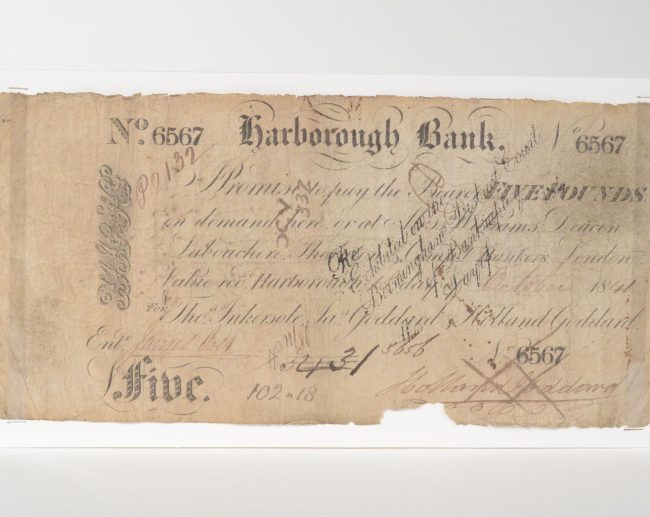

Harborough Bank note

During the latter half of the 18th century, some 800 country banks were established in Britain, usually by well-established tradesmen or wealthy landowners. Harborough’s first bank was opened on Tuesday (which was market day) 27th of December 1791 as the Bosworth & Inkersole Bank. George Bosworth (1735-1804) was a prosperous ‘gentleman grazier’ and Thomas Inkersole (1751-1820) ran a successful ironmonger/cutler business in the High Street.

During the second half of the 18th century, Market Harborough was a thriving market and coaching town. The A6 main road from London to the north of England ran through the town and it was a good stop-over place for stage coaches, being mid-way between Northampton and Leicester. Traffic had been steadily increasing over the previous century and markedly so since roads had been improved via turnpike trusts. Local people took full advantage of the situation particularly through its coaching inns, ale houses and shops. There were also numerous successful trades within the town, principally those relating to cloth manufacture, shoemaking and other leather trades.

Since the enclosure of the open fields in 1776, local agricultural interests had prospered and so did those businesses associated with farming and the growing coach trade, particularly the care of hundreds of horses.

One sign of prosperity was that six more annual Market Fairs had been added to the town’s long established October Fair bringing hundreds of visitors to town. Such prosperity generated large amounts of money that needed better security than peoples own homes. As such, a bank was needed.

Bank of England notes were in circulation in the late 18th century, but most private banks printed their own notes – apparently people preferred (and trusted) the local bank notes to those from London!

George Bosworth’s involvement with the bank was short-lived as he dissolved the partnership on 5th of September 1794 (reasons unknown). Thomas Inkersole re-named the business Harborough Bank and ran the bank on his own until 1807 when two of his nephews, Holland Goddard and James Goddard, joined him.

Harborough Bank prospered, although competition arose when Market Harborough Savings Bank opened on 28 April 1838.

On 22nd of April 1843, news broke that a Leicester bank, Mitchell, Clarke & Philips had ceased trading. This caused a run on Harborough Bank who announced insolvency two days later. In total the bank had liabilities of £194,000 but assets of only £130,000, leaving a deficit of £64,000. It transpired that Clarke’s carpet factory owed Harborough Bank £89,000 in unsecured loans! The bank had 510 creditors, many being local people who must have suffered considerable hardship. Creditors eventually (sometime around 1860) received 10/- in the pound from the Bankruptcy Court.

Clarke’s factory closed two months later, throwing 300 people out of work.

Canal jug

Narrowboats in the 19th century were commonly decorated with bold, colourful roses, castles and romantic landscapes. The decorations covered not only the boat’s exterior but effectively everything inside as well, from the kitchenware to the furnishings and even the horse’s harnesses.

The ‘roses and castles’ style came into fashion during the industrial revolution, when other traditional crafts were being replaced by mass production. It is not known precisely where the tradition originated from; however, there are clear influences of gypsy culture and similarities to folk art from Germany, Holland and even Asia.

The bright, cheerful decorations, unique to each artist, were a sign of pride for people working on the canals and solidarity with their fellow boaters.

The tradition still lives on today; a campaign has commenced in Britain and France to revitalise the run down early industrial canals and so too the art.

Foxton Locks, near Market Harborough, is the largest flight of staircase locks on the English canal system, with ten locks and side ponds on a hill – this allows canal boats to travel up and down the hill.

Building work on the locks started in 1810 and took four years to complete. In 1900 an incline plane was built to resolve the operational restrictions imposed by the lock flight. While this was in operation, the locks were not maintained and fell into decline. In 1908 the canal committee donated £1,000 towards renovations. However, the incline plane was not a commercial success and only remained in full-time operation for ten years; It was dismantled in 1926.

Today, the locks are a popular tourist attraction. The Foxton Canal Museum is located in the former boiler house for the plane’s steam engine and covers the history of the locks, the planes and the lives of the canal workers.

Gloster-Whittle prototype jet engine

The Gloster-Whittle jet engine was invented by Sir Frank Whittle. Whittle was born in Coventry in 1907 and was taken on as an apprentice in the RAF in 1923, qualifying as a pilot in 1928.

Whilst a cadet, he wrote a thesis arguing that a plane’s fastest airspeed and longest range could only be achieve when flown at extremely high altitude; because the air is thinner and less resistant. Standard piston and propeller engines were unsuitable for this, so he suggested that rocket propulsion or propellers powered by gas turbines should be used instead. Whittle went to the Air Ministry with his proposal, but he later patented the idea himself after they turned him down.

In 1936, Whittle secured financial and RAF support, and founded Power Jets Ltd in Rugby. There, he began constructing a test engine, which – after a false start – completed its first flight in 1941.

The engine for Britons first jet aeroplane, the Gloster E.28/39 (also referred to as the Gloster-Whittle), was made in Lutterworth. A memorial statue of the aircraft can be seen on the Whittle Roundabout, south of the town, in celebration of Lutterworth’s aeronautical heritage.

Further displays

Born and bred

Read more about 'Born and bred'

Growing up

Read more about 'Growing up'

Living off the land

Read more about 'Living off the land'

Made in Harborough

Read more about 'Made in Harborough'

Market Harborough and the District

Read more about 'Market Harborough and the District'

Places to go, people to see

Read more about 'Places to go, people to see'

Religion and belief

Read more about 'Religion and belief'

Sickness and health

Read more about 'Sickness and health'

Sounds of Battle

Read more about 'Sounds of Battle'