Sounds of Battle

Sounds of Battle is part of the following collections: The Harborough Collection.

Highlights

Letter from an American Serviceman

A touching story of friendship during the Second World War

View object

Kruger Medal

The ‘Kruger Medal’, fashioned by a Boer prisoner of war (POW), depicts Paul Kruger, President of the Transvaal or South African Republic (SAR) from 1833-1900. After the British annexation of the Transvaal in 1877 and the First Boer War (1880-1881) Kruger became the focal point and personification of Afrikaans independence in South Africa. Throughout his time in office Kruger had dealings with Benjamin Disraeli and Cecil Rhodes in trying to obtain a mutually beneficial agreement with limited success.

Fashioned by a POW, this medal was most likely made during the Second Boer War, also referred to as the South African War (1899-1902), when concentration camps were employed by colonial British forces to combat the guerrilla fighting which broke out in 1900. Despite early Boer successes during the British dubbed ‘Black Week’, by 1900 British colonial reinforcements and weight of arms ensured the British had captured all major Boer cities. With the war transitioning from conventional to guerrilla means, Kruger was forced to flee to Europe and Kitchener was appointed to tackle the increasingly effective Boer guerrilla war by employing scorched earth tactics and concentration camps, sparking vehement protests in Britain after approximately 26,000 non-combatants were killed during their incarceration.

Set within the context of the declining power of the British Empire in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century the Second Boer War, or the South African War, served to highlight both the resolve of the empire and its waning strength. Prior to the Second Boer War, Britain’s prestige and power was seen as unequivocal, with the military inadequacies highlighted by the Second Boer War in terms of leadership and recruitment quality, Britain’s power was beginning to be questioned.

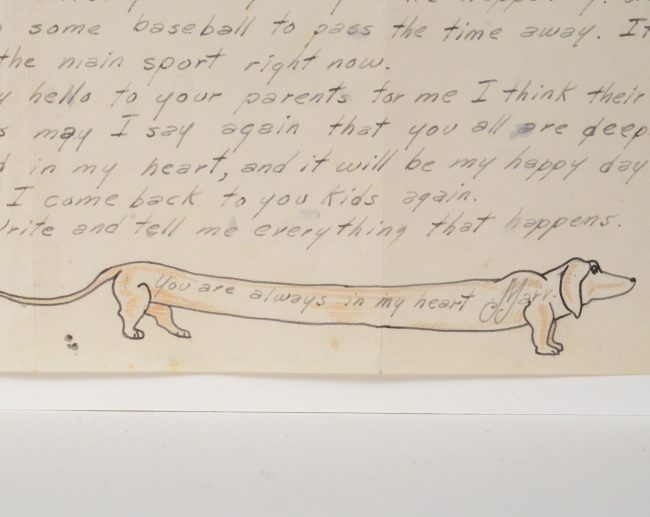

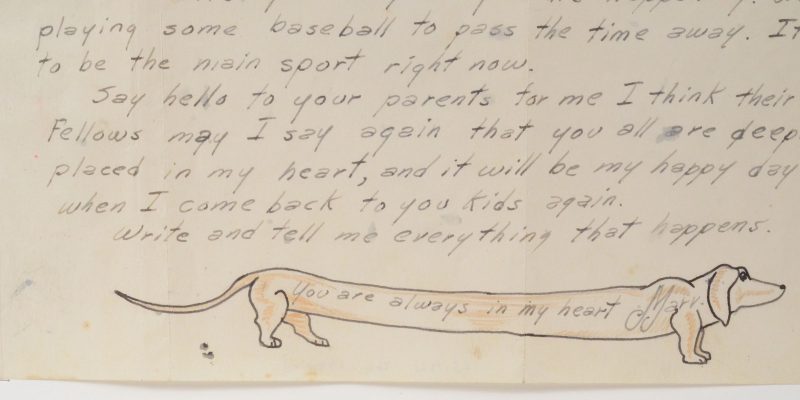

Letter from an American Serviceman

This letter is full of Americanisms in both language and images – the highly stereotyped, Hollywood-style “Red Indian” at the top, and the use of words like “swell” and “gee” leave us in no doubt as to the writer’s country of origin. It is clear he made good friends with the children he is writing to, saying, “…you are all deeply placed in my heart and it will be my happy day when I come back to see you kids again.”

Interestingly, he also writes, “Fellows my letters will be dull for a while, because I can’t write you anything that’s happening.” Given the date of the letter, this is probably a reference to Operation Overlord – the D-Day landings in Normandy, 6th June 1944. In the early months of that year, thousands of American service personnel arrived in Leicestershire and Northamptonshire in preparation for D-Day. For many local people, this was the first time that they had encountered Americans and American culture outside of the cinema.

What is intriguing about the letter is that it raises many unanswered questions. We know the writer of the letter is called Marv, but we do not know his story, where he came from, how he meet the children he is writing to or what happened to him on D-Day. Marv’s beautifully illustrated letter is a wonderful example of friendship in a terrible time of conflict.

Ration books

Before the Second World War Britain relied heavily on imports of food from around the globe, principally America, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. One of Germany’s military aims was to sink merchant shipments and ‘starve Britain into submission’. Thousands of British merchant ships were lost, food became scarce, and rationing was introduced in January 1940.

The Dig for Victory campaign was organised by the Ministry of Agriculture. It called for everyone in Britain to ‘do their bit’ by digging up their lawns and flower beds to plant vegetables. They also encouraged people to keep an allotment; 1.4 million allotments were established which produced over 1 million tons of vegetables. People were also encouraged to keep chickens, rabbits, goats and even pigs in their back-gardens or small-holdings.

The system of rationing was introduced early in the war. Each person was presented with a ration book containing coupons and every householder was required to register with their local shops. Shopkeepers were provided with enough food for their ‘registered customers’.

Initially, only bacon, butter and sugar were rationed, but this was soon followed by meat, fish, tea, jam, biscuits, breakfast cereals, cheese, eggs, milk and canned fruit. Later during the war, other goods such as clothing and shoes were rationed.

Although most people considered rationing to be fair, it was far from perfect and illegal black-markets flourished.

Women's Land Army

The Women’s Land Army (WLA) was formed out of necessity in 1917 during the First World War as a means to replace men leaving land work to join the military. The WLA concluded at the end of World War 1.

In June 1939 the WLA was reformed when the Second World War was imminent. Initially, the government relied on volunteers, but conscription was required from January 1942.

Market Harborough’s local WLA attachment was based at a purpose-built hostel in Lubenham. There were around 700 hostels in Britain. The Lubenham hostel could accommodate 40 ‘land girls’ to serve farms in the Welland Valley.

‘Land girls’ were expected to undertake all aspects of farming under the direction of the farmer. The work was arduous, and the hours were long; up to 50 hours a week in the summer. ‘Land girls’ were paid 28 shillings a week; however, men doing the same job were paid 38 shillings a week. Killing rats was an essential part of their work, one local girl reported killing over 200 in one day!

Prisoners of war (POW’s) were regularly assigned agricultural work and frequently worked alongside the ‘land girls’. The arrangement worked well until it was discovered that POW’s were receiving higher quality food, the ‘land girls’ threatened to go on strike. Their threats were successful and resulted in better working conditions.

Although many of the ‘land girls’ were far from home and loved ones, they could enjoy the camaraderie of their shared work and enjoy their time off; especially when the Americans arrived to undergo training for D-Day.

The Women’s Land Army continued their work even after the war had been won in 1945. Food rationing continued after the war, and the WLA remained active until 1950 when it was disbanded.

The WLA consisted of over 90,000 women working the land, and their hard work kept Britain fed for the duration of the war. Although Britain required rationing, no one starved as a result of the war; in spite of Germany’s best efforts to prevent oversea food importation and ‘‘starve Britain into submission’’.

Further displays

Born and bred

Read more about 'Born and bred'

Growing up

Read more about 'Growing up'

Living off the land

Read more about 'Living off the land'

Made in Harborough

Read more about 'Made in Harborough'

Market Harborough and the District

Read more about 'Market Harborough and the District'

Market Harborough Historical Society

Read more about 'Market Harborough Historical Society'

Places to go, people to see

Read more about 'Places to go, people to see'

Religion and belief

Read more about 'Religion and belief'

Sickness and health

Read more about 'Sickness and health'